Greensboro's Two Downtowns; A Failing Gentrification with Office Vacancies and Remote Work Compounded with the Surrounding Poverty-Stricken Reality

A downtown built for outsiders, abandoned by workers and disconnected from its neighbors

Downtown Greensboro is split between an aspirational gentrification vision and the reality of surrounding deep poverty, creating an economic and social mismatch redevelopment failed to resolve.

Remote and hybrid work permanently hollowed out the commuter-based office economy, collapsing daily foot traffic and discretionary spending downtown businesses depended on.

Office vacancy rates above 20% signal a structural failure, not a temporary downturn, undermining the justification for upscale retail, restaurants and Class A office development.

Public and private investment continues to target affluent outsiders, while nearby low-income and majority-minority communities are effectively excluded from participation.

Covid exposed, rather than caused, downtown’s weaknesses, leaving Greensboro chasing a past economic model that no longer exists.

The narrative of downtown Greensboro is one of stark contradictions. While new investments aim to reshape its identity, the foundational reality of the surrounding community, marked by significant poverty and homelessness, remains visibly present and doesn’t appear to be going anywhere.

Simultaneously, one of the economic engines meant to justify this transformation, downtown Greensboro’s discretionary higher income spending office worker core, is experiencing a historic downturn as remote work and professional business vacancies hollowed out the daily flow of spending at local retail establishments. This confluence of factors has left the heart of the city in a precarious state, struggling to reconcile the aspirational future advocated by Greensboro’s wealthiest elite property and business owners with its existing identity and economic reality of what’s actually happening on the ground.

A Downtown Ringed by Economic Hardship

The advertised vision for downtown excludes the existing low income community surrounding two thirds of it.

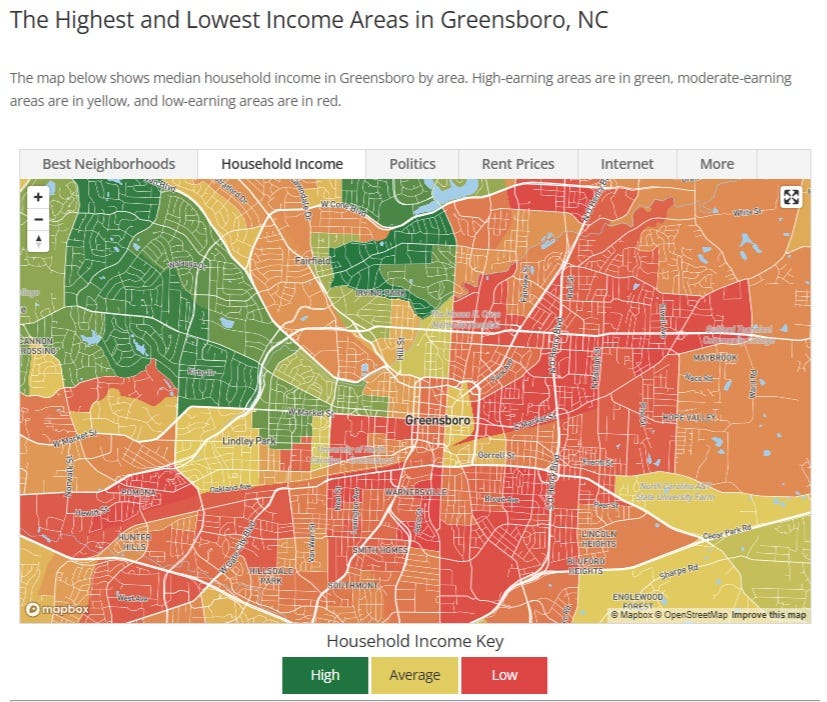

Understanding downtown’s challenge begins with the demographics of the community it sits within. A closer look at income reveals a concentration of poverty around the urban core Greensboro’s elites want to revitalize and profit from.

Significant capital is being spent to attract affluent outsiders to an area defined by deep, concentrated poverty, while the existing community is economically stranded and is effectively forced not to participate.

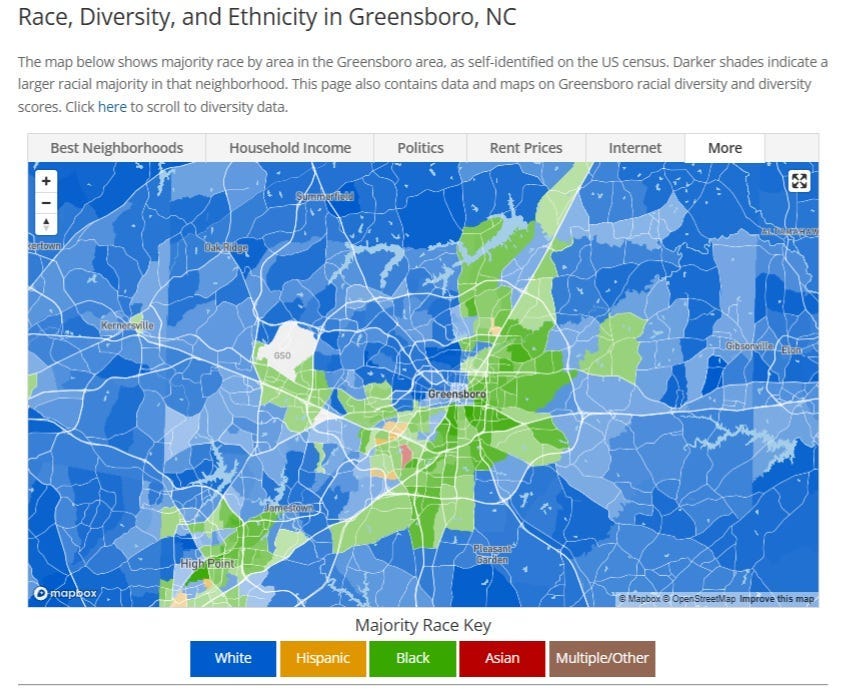

Data shows zip code 27401, which encompasses much of downtown Greensboro, has a poverty rate of 28.9%, more than double the national average and the highest rate in the city. This high concentration of poverty geographically frames the downtown area, creating a pocket of massive redevelopment efforts relatively far away from Greensboro’s higher income, mostly white populations who enjoy free parking and conveniences close to home. The gentrification effort isn’t occurring in a “transitional” neighborhood but is an attempt to forcibly pivot the economic identity of what was a busy downtown idolized in a prior century but is now next to the city’s poorest, mostly minority communities.

The Race Map’s “Majority-Minority” Core; This high-poverty area overlaps significantly with downtown-adjacent neighborhoods shaded for Black and Hispanic majorities, showing the intersection of economic and racial segregation. Downtown Greensboro is the ‘pocket’ in the middle, surrounded by many who realistically, aren’t invited to the party, as it’s relatively unaffordable, and if you’re homeless, you can’t sit, eat or sleep etc...

The race map defines the exact geographic target; the central, whiter downtown zone. Here, millions in public and private funds are spent on amenities, upscale housing and commercial spaces designed for a wealthy demographic who can afford Tanger Center tickets. This effort falters as office vacancy soars above 20%, evaporating the reliable customer base and revealing the fragility of an economy built for commuters.

The powers that be have been counting on higher income households living, working, traveling and spending time and money where most don’t live or feel comfortable.

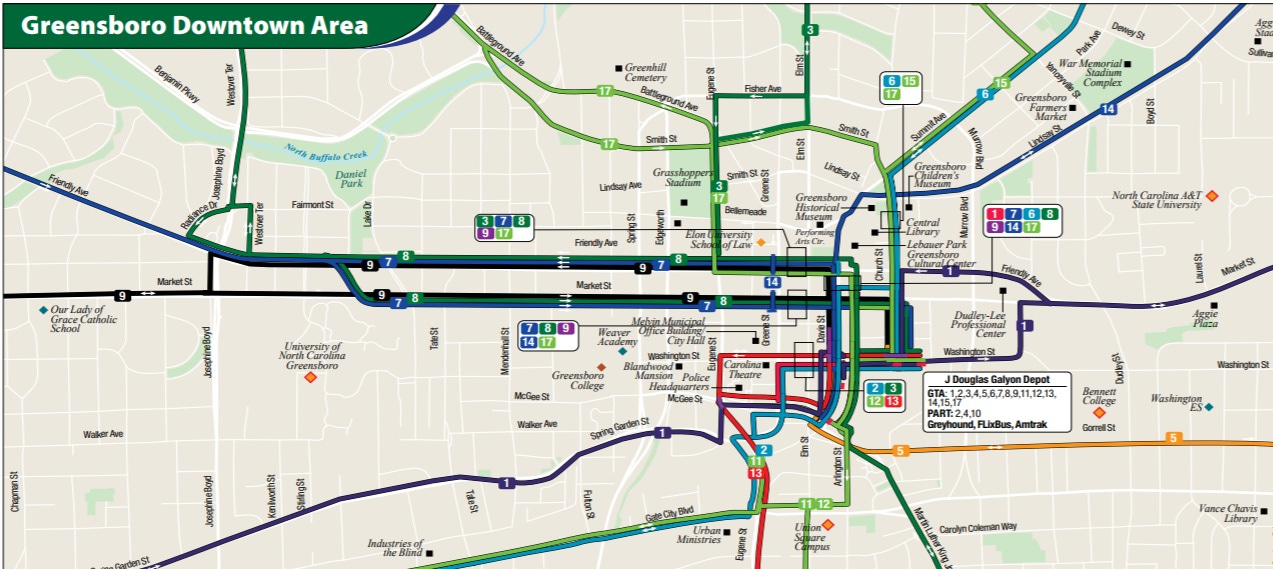

Downtown Homeless Services and Low Income Transportation Hub

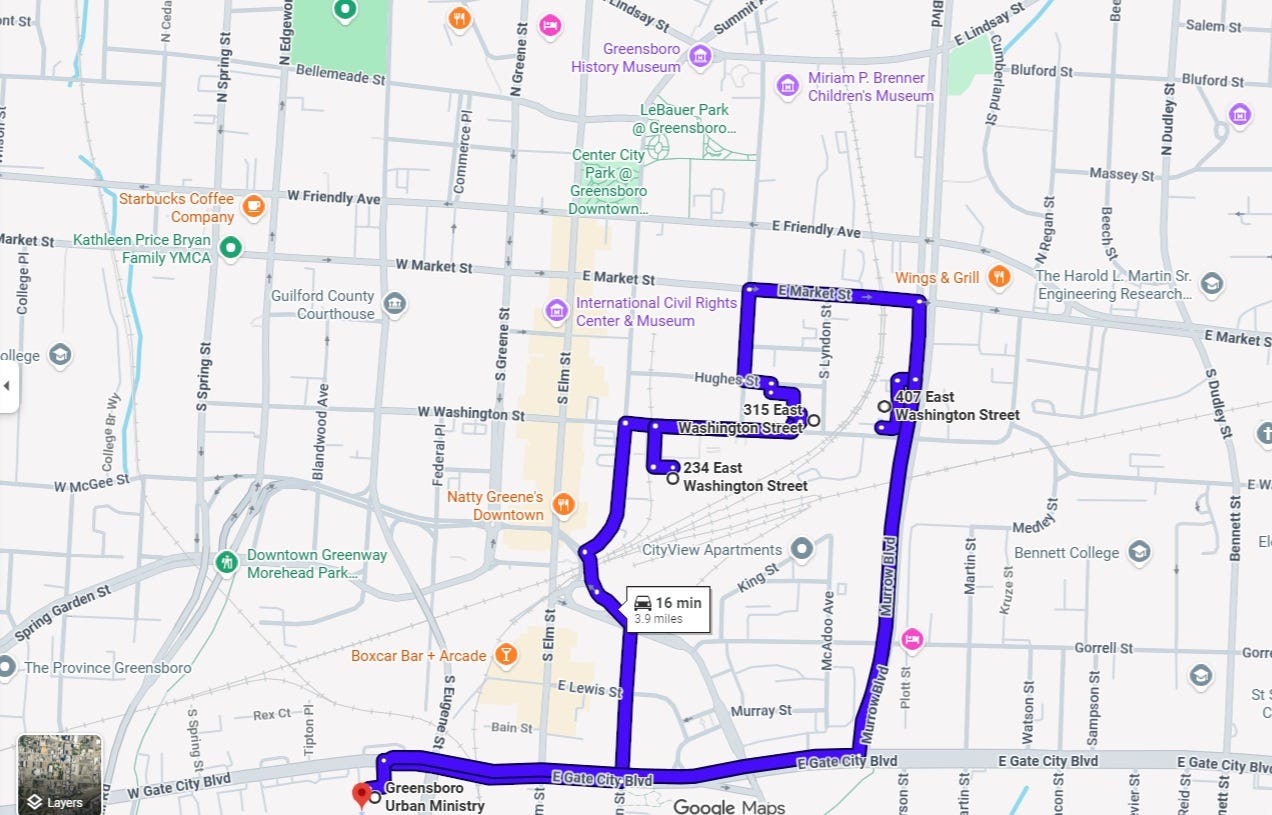

Central to the physical and social landscape of downtown is the Greyhound, Amtrak and Greensboro bus transportation hub at the Gaylon Depot at 234-236 East Washington Street.

The Interactive Resource Center (IRC) at 407 E Washington Street is close by, and is a central day center offering showers, laundry, mail service and case management for people experiencing homelessness.

Family Service of the Piedmont at 315 E Washington Street offers support services for families in crisis, including mental health and financial stability programs.

Greensboro Urban Ministry, located just behind the corner of Gate City Boulevard and Eugene Street offers 100 beds for single men and women, and free, hot lunches daily to anyone in need.

This concentration of services means a steady, visible population of people in need circulates in the downtown area, a reality that often clashes with visions of Class A commercial office properties, high end hotels with an adjacent ball park, an upscale residential district and a first class performing arts center.

The “stakeholders” have spent millions of their own and everyone else’s taxpayer monies on their properties etc..., trying to gentrify downtown to the point where there aren’t any ‘undesirables’ around the area, but can’t be done without keeping a whole lot of poor, mostly black folks away from where, for instance, Downtown Greensboro Inc.’ board of directors, want to make money.

Center City and LeBauer Parks are great examples. As they are free and within walking distance of homeless centers and mostly black low income neighborhoods, that’s who hangs out there, as opposed to what DGI and its members want. Chances are, most of the condo owners in Roy Carroll’s Center Point tower probably don’t frequent the park across the street much.

A lot of wasted taxpayer money has been flushed; ‘Leaders’ need to realize downtown can’t really be changed to the way the property owners want it to unless many of the people they don’t want there are removed or moved, not that they haven’t been trying;

The Post-Covid Effect; A Permanent Structural Shift, Not a Temporary Dip

Covid did not merely disrupt downtown Greensboro; it accelerated and locked in changes that undercut the entire economic logic behind its redevelopment strategy.

Before 2020, downtown’s fragile ecosystem depended on a predictable rhythm; office workers commuting in five days a week, buying lunch, paying for parking, lingering after work for drinks, events or errands. That daily, middle-to-upper-income presence masked the deeper weaknesses of high surrounding poverty, limited residential density with spending power and an overreliance on commuters who did not actually live downtown.

Covid broke that rhythm permanently.

Remote and hybrid work models hollowed out the weekday population downtown businesses were built around. Office leases may still exist on paper, but utilization does not. A building that is 80% leased but only 30–40% occupied on any given day might as well be vacant from the perspective of restaurants, coffee shops and retailers. Payroll is gone. Foot traffic is gone. Parking revenue is gone. The “lunch rush” that justified high commercial rents no longer exists.

This is not a cyclical downturn, it is a structural collapse of demand.

Downtown Greensboro’s redevelopment model assumes white-collar professionals will once again commute en masse, tolerate rising parking fees, spend discretionary income and coexist comfortably with visible poverty and homelessness. That assumption no longer holds. Professionals with remote options now optimize for convenience, safety, and cost; factors which overwhelmingly favor suburban offices, home offices or mixed-use nodes closer to where they live.

As a result, downtown retail is being asked to survive on weekend traffic, special events, and aspirational tourism, an impossible task for businesses with daily fixed costs.

At the same time, inflation and rising household costs have reduced discretionary spending across all income levels. Even those who still come downtown are spending less, staying shorter and being more selective. Higher parking rates, enforcement expansion and shrinking free options further discourage casual visits, especially when suburban alternatives offer free parking and fewer friction points.

Meanwhile, the visibility of homelessness and poverty, never addressed structurally, has become more pronounced as fewer office workers dilute the street population. What once blended into a busy downtown now defines it visually. This feeds a perception loop; fewer workers lead to emptier streets, emptier streets heighten discomfort, and discomfort drives even more people away.

The result is a downtown economy trying to operate as if it were 2015, using tools designed for a commuter-centric past that no longer exists.

Public and private capital continues to chase a shrinking demographic, affluent outsiders, while ignoring the reality that the surrounding population is poorer, more transit-dependent, and largely excluded from the consumption-based vision being sold.

Covid didn’t create that mismatch; it exposed it.

Downtown Greensboro is no longer failing because of temporary headwinds. It is failing because the foundational assumptions behind its redevelopment; who will come, why they will come and how often, no longer reflect how people live and work in a post-Covid economy.

Until that reality is acknowledged, additional spending on amenities, branding and “activation” will continue to function less as revitalization and more as an increasingly expensive denial strategy.

Unfortunately Related;