What Greensboro's City Council Didn't Do

Two Standards of Ethics; Why Guilford County Enforces Conflict-of-Interest Law, and Greensboro Doesn’t

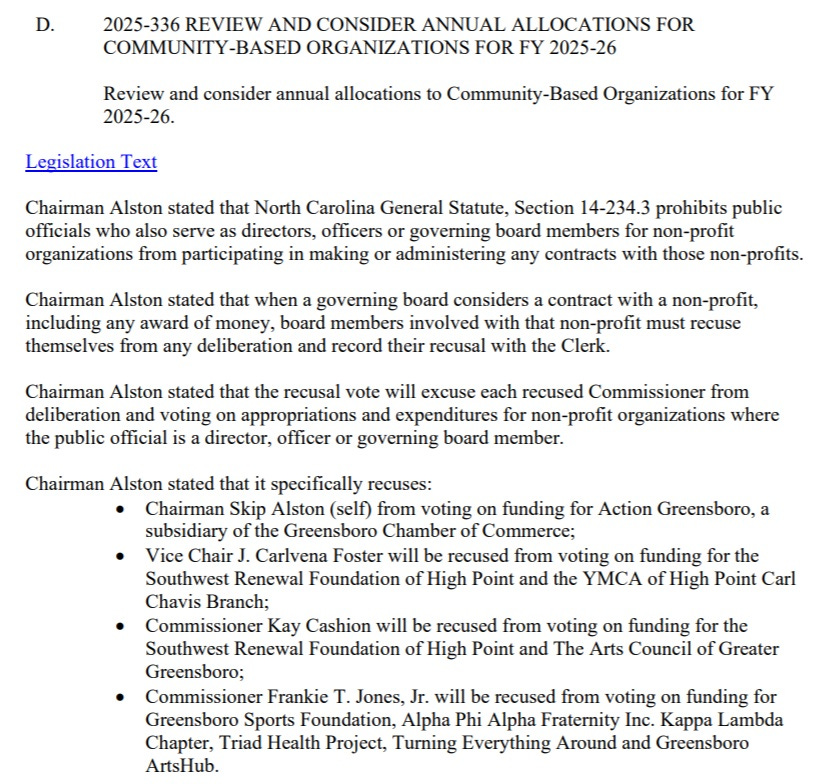

On June 18, 2025, the Guilford County Board of Commissioners took a small but crucial step to uphold public trust. Before voting on its budget, the board recused Chairman Skip Alston and Commissioner Frankie Jones from deliberating or voting on appropriations for nonprofits where they serve as board members. Citing North Carolina General Statute §14-234.3, which prohibits public officials from “participating in making or administering any contract” with a nonprofit where they hold a governing role, the Commission unanimously approved a formal recusal motion.

Chairman Alston stated clearly that “when a governing board considers a contract with a nonprofit, including any award of money, commissioners involved with that nonprofit must recuse themselves from any deliberation and record their recusal with the Clerk.”

Greensboro City Council Did the Opposite

Just one day earlier, on June 17, 2025, the Greensboro City Council voted 9–0 to adopt the Fiscal Year 2025-26 budget — which included public funding for several nonprofits where sitting council members hold leadership positions.

Among them;

Mayor Nancy Vaughan, Councilmember Tammi Thurm, and Councilmember Zack Matheny each serve on the Greensboro Downtown Parks board, which received funding in the same budget they approved.

Councilmember Hugh Holston, the Executive Director of the Greensboro Housing Coalition, did not recuse himself despite the organization being a direct contract recipient.

Without recusal, Marikay Abuzuaiter voted to fund the Greensboro Sports Commission, on whose board she serves with County Commissioner Frankie Jones, without recusal.

Councilmember Zack Matheny, the paid CEO of Downtown Greensboro Inc. (DGI), voted to fund his own organization — a direct financial interest that would clearly trigger the recusal requirements outlined in N.C.G.S. §14-234.3 and the City’s own Conflict of Interest Policy (B-22).

When questioned during the meeting, Matheny briefly consulted with former Deputy City Attorney Tony Baker, who publicly stated there were “no conflicts” and advised that Matheny could vote. The council then passed the budget unanimously, without a single recusal.

The Law and the Policy

Greensboro’s Conflict of Interest Policy (B-22), effective June 1, 2018, explicitly states:

“No officer, employee or agent of the City shall participate in the selection or in the award or administration of a contract supported by federal, state, or city funds if a conflict of interest, real or apparent, would be involved.”

It further defines a conflict as existing when an officer or their employer “has a financial or other interest in the firm selected for the award.”

State law is even more direct. N.C.G.S. §14-234.3 forbids public officials who serve on nonprofit boards from participating in contracts, appropriations, or funding decisions involving those same organizations. The Guilford County Commission followed that rule to the letter. Greensboro City Council ignored it.

Two Governments, Two Standards

The same ethical process repeated on July 17, 2025, when the County Commissioners again recused Alston, Jones, and several other members from votes concerning nonprofits they were connected to. The result: a transparent, unanimous 8–0 vote affirming compliance with state law and ensuring public officials did not participate in funding decisions involving their own organizations.

In neighboring chambers, under the same state statute, two different governing bodies took two very different approaches to ethics.

The County Commissioners acted to protect public confidence and comply with law, recording recusals in open session and allowing separate votes on affected items.

The City Council, by contrast, permitted members to vote on budgets directly benefiting the organizations they run or govern with the City Attorney’s office blessing the practice as conflict-free. They did it again on Tuesday night.

The contrast could not be sharper. Where the County took the high road of transparency and recusal, Greensboro’s leadership chose convenience and self-interest, eroding public trust and raising questions about whether ethics policies are applied selectively.

Why It Matters

Public ethics laws are not optional guidelines; they exist to ensure decisions about taxpayer money are made impartially and without self-dealing. When public officials vote to fund their own organizations, or those led by their colleagues, it violates the spirit of fairness and independence that both state law and Greensboro’s own ethics code demand.

As the County has demonstrated, recusal is not a punishment, it’s a safeguard. It preserves the legitimacy of public decision-making. Until the Greensboro City Council enforces its own rules and the state’s ethics statutes with equal rigor, every vote involving public-private partnerships will remain clouded by the appearance, if not the reality, of corruption.