Guilford County and Greensboro Real Estate Revaluation Driven Tax Increases Function as a Tax on Unrealized Gains

We Didn’t Sell or Profit. But We are Going to Owe More.

When our local governments raise our tax bills as our houses went up in value even though overwhelmingly most homeowners didn’t sell them, it’s a tax on unrealized gains. The values are determined by hidden, copyrighted calculations of a a private company, so there’s no real way to know what actually happened behind the closed doors of Guilford County’s Tax Department.

If a stock goes up in value, you don’t owe taxes until you sell it. If your retirement account grows, the IRS doesn’t send you a bill just because the market had a good year. But if your home value rises on paper, the county and cities can immediately raise your tax bill even though you haven’t made a dime.

In Guilford County, a 70-year-old widow still living in the home she shared with her husband. The house isn’t paid off ; she still carries a mortgage. Her income is Social Security, and she works a small part-time job to keep up with monthly bills. Last year, her home was taxed on a value of $246,400 and her county bill was $1,799.95.

After revaluation, the assessed value jumped to $383,500; a 55% increase, well above the approximate county average of 42.5%. Even if commissioners adopt a revenue-neutral rate, her bill would still rise to about $1,965, roughly 9% more. If Guilford County approves a 10% increase above revenue neutral, as a tax hike has been forewarned by some commissioners, her bill would climb to about $2,164, more than $360 higher than last year, a roughly 20% jump.

Because she has a mortgage, that increase doesn’t just show up once a year; it hits her monthly escrow payment. And as some values rise, so does homeowners insurance, pushing that escrow payment even higher.

She doesn’t want to sell her home. She didn’t get a raise, yet her monthly housing cost goes up anyway, not because her income improved, but because the paper value of her home did.

She hasn’t sold it. She hasn’t realized any gain. But her tax bill jumps hundreds, because of “market appreciation” she hasn’t realized.

That increase isn’t based on income.

It isn’t based on ability to pay.

It isn’t based on improvements.

It’s based entirely on a paper gain.

That’s a tax on unrealized wealth, which in the case of private residential properties, is shelter.

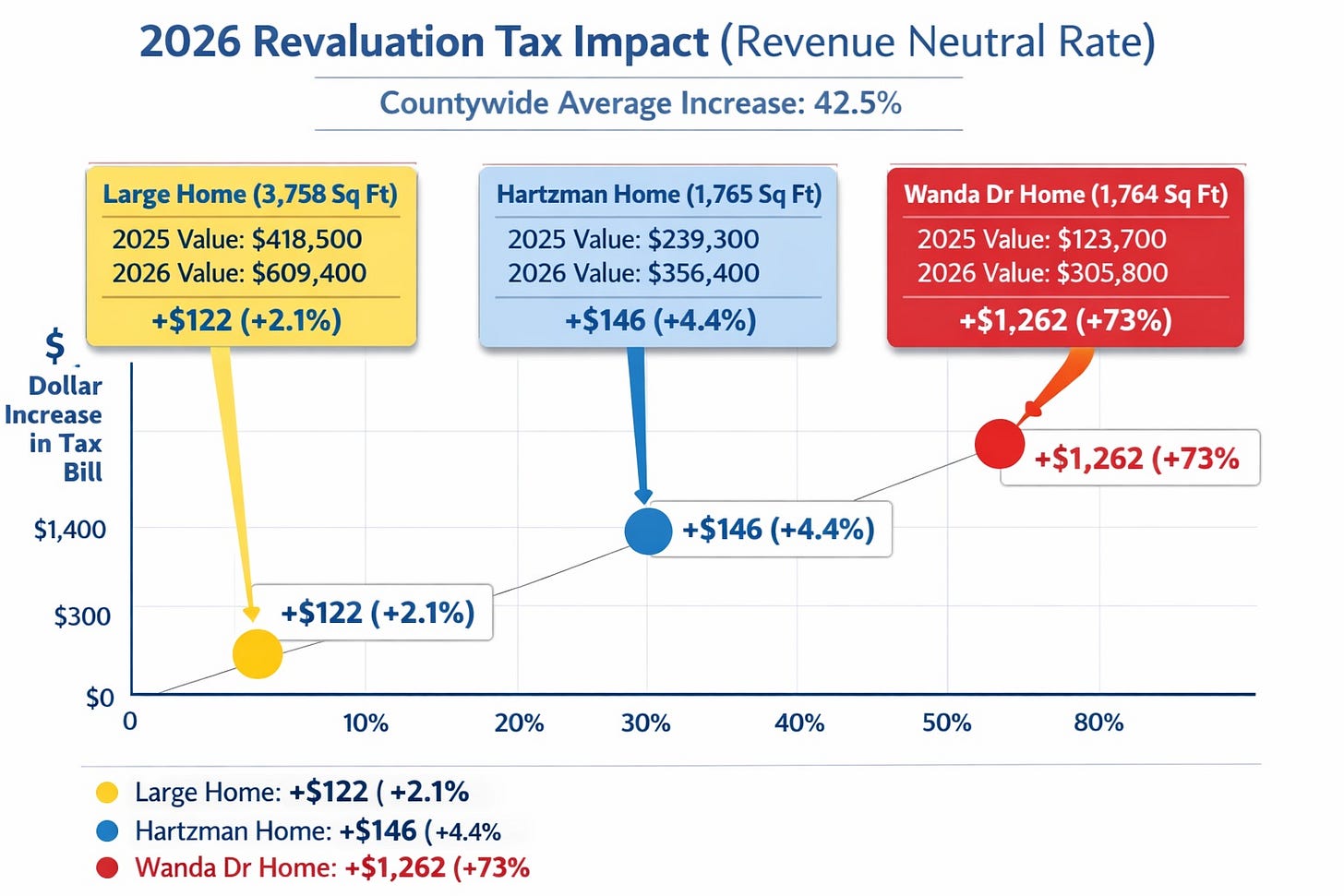

Here’s the mayor of Greensboro’s house, my house, and another across town;

“Revenue-neutral” only offsets the average increase. Properties that went up far more than the average end up paying a much larger dollar and percentage increase.

Meanwhile;

Larger homes with smaller relative increases (like the 3,758 sq ft property) barely see their bills rise.

If the average is about 42.5%, many, likely higher valued homes, are going to see a fall in value, as in a tax cut for the wealthy at the expense of the poor.

Mid-sized homes like mine take a moderate hit, slightly above average.

This is a classic example of vertical inequity in property tax revaluations;

Lower-priced, previously undervalued homes can get hit the hardest.

Higher-priced homes often see only minor increases, even if their nominal values are huge.

Landlords pass the tax increases on to their tenants.

It shifts the burden downward, despite the “neutral” label.

Despite a “revenue-neutral” valuation adjustment by Greensboro and Guilford County, the 2026 revaluation reveals a stark reality; homeowners with smaller or previously undervalued properties are facing the largest tax increases, while larger or already high-value homes will likely see only modest changes.

For retirees, long-time homeowners and working families in appreciating neighborhoods, it can feel like a slow squeeze; pay more every year or eventually cash out and move.

Revenue-neutral or not, when revaluations produce large spikes for certain homeowners, the practical effect is the same; government is taxing equity that exists only on paper.

If policymakers want to defend that system, they should at least acknowledge what it is, and explain why a retired homeowner on Social Security should owe more taxes simply because a black box says her house is worth more this year than last.

Related;